Harvest is in: Farmers, buyers play waiting game

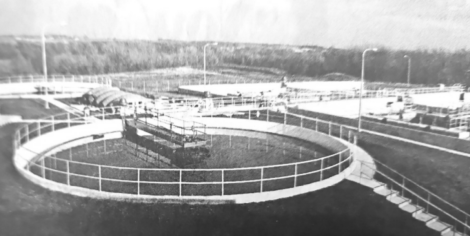

It was a typical scene at elevators during the harvest season,which now is about ended. Superb weather made for a fast combine job on soybeans and corn, and there was a rush on elevator facilities. (Photo by Art Hanson)

They’re all playing a waiting game.

Farmers are waiting for grain prices to go up, buyers are waiting for the price to drop lower, and the government is waiting to see the result after placing an embargo on grain sales to foreign buyers.

What it means is that grain is moving out from elevators with the speed, at best, of a trickle.

In southern Minnesota many elevators have been forced to pile corn on the ground in spite of the fact that this fall’s harvest is less than normal.

ONE ELEVATOR that has piled corn is the Sanborn Farmers Elevator. Elevator Manager Dick Dummer said the yellow mound totals about 30,000 bushels.

The Sanborn area was hard hit by drought this year,with normal corn yields of better than 100 bushels per acre cut to a 1975 harvest average of about 60 bushels per acre, Dummer said.

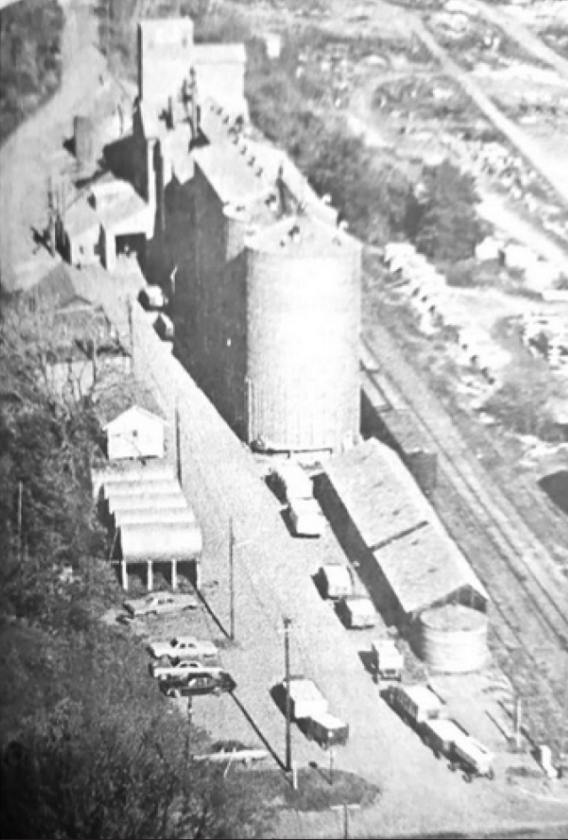

The piled corn at Sanborn is surprising not only because of reduced yields, but also because the Sanborn elevator is a member of the Southern 7 Cooperative Elevator east of Springfield.

The terminal was built by seven elevators to improve grain transportation by loading 50-and 100-car unit trains.

“The price just isn’t high enough,”Dummer said. “Farmers are holding on to their grain.”

AND THE buyers aren’t buying.

The big buyers are fully aware of what may be record corn and wheat harvests nationwide and are sitting back waiting for the excess supply to drive prices downward,says Robert Swanson, marketing development representative and information officer for the state Department of Agriculture.

“They’re buying what they need to keep their operations going,” he said. “They’re waiting out the farmer.”

Elevator managers are in the middle, taking a guarded stance.

“Of course we always like to be full,” said Dummer.

Farmers must pay storage costs for elevator-stored grain, and the longer the grain stays around the more money the elevator makes and the higher the year-end dividends to its patrons.

BUT THE elevators are also dependent on the longer range financial health of their members. “The farmers want a good price no matter how it comes,” Dummer said. “They look at their cost of production and their yields and they’ve got to have it.”

Slightly more than one year ago (mid-October, 1974) in the Minneapolis cash grain market corn topped at $3.34 and soybeans at $8.15.

MANY FARMERS have held on to their grain since about that time,says Wanda Farmers Elevator Manager Fritz Bleess.

Prices at the Wanda elevator Friday morning were $2.41 for corn and $4.62 for soybeans, down two cents and five cents, respectively,from the day before.

“We’re going to have to get corn to get up to $2.80 and beans to $5 or $5.50,” Bleess said. “But I can’t see it getting up there. (The farmers) are going to have to start selling.”The Wanda elevator manager characterized the situation as “pretty sick,” but noted that the elevator, long nagged by a problem of insufficient availability of rail transportation on its branch line,is now getting an ample supply of cars.

AGGRAVATING the lack of grain movement are two more factors: decline in feedlot inventories and the government embargo on foreign grain sales.

“There’s no movement on the feeding front,” Swanson said.”The state has its lowest number of cattle on feed in many years.”

The number of cattle and calves on feed at the present time in the state is 290,000-down 9 per cent from the 320,000 on feed a year ago.

“Livestock producers are not buying in any significant volume,”he said.” Livestock prices are still unattractive and unprofitable. You’ve got to feed a steer six to eight months. It’s extremely risky.”

If grain prices continue to drop,the livestock market may rebound as a buyer, Swanson noted.

“Agriculture is in a bind now where one segment gains at the expense of the other,” he said.

WHAT MAY occur is a turnabout.

With livestock producers growing hesitant to feed $3 corn to their animals corn grew in importance as a cash crop, but fortunes may be changing, Swanson notes.

Citing an Aug. 8 report from the University of Minnesota, he says the average Minnesota farmer must get $3 a bushel just to break even.

The University computed that this year it costs about $210 to put in an acre of corn. Based on Oct. 1 state crop yield estimates, the state average this year is about 71 bushels per acre, amounting to an average cost of $3 per bushel.

It means the average Sanborn area farmer is losing about $1 a bushel at current prices.

SOME FARMERS feel the government should remove the current embargo on foreign grain sales to improve prices and grain movement.

Illinois’ State Agriculture Director Robert Williams blamed the embargo for “the logjam at the elevators.”

The government “is calling for full production on the one hand and embargoing sales overseas on the other,” he charged.

The Illinois man also said that the government action will mean higher prices for consumers.

“We had a bumper crop this year,” he noted, “and while that means more grain to be harvested, it normally would also mean that there would be a break for the consumer. The savings consumers would have realized are being eaten up by the storage costs incurred.

The stagnation of movement, he said, has widened the gap between the price a farmer is paid for his corn and the price paid at the Chicago Board of Trade from a normal gap of 10-12 cents to 50-60 cents.

New Ulm Daily Journal

Nov. 3, 1975