Recounting the star-guided Pacific voyage

New Ulm Marine veteran Stephen Somsen explained celestial navigation and wayfinding methods used by Polynesian voyagers during his presentation Monday night.

NEW ULM – Marine veteran and New Ulm native Stephen Somsen spoke last week at the New Ulm Public Library, offering a firsthand account of a landmark 1980 voyage aboard Hokulea, a traditional Polynesian double-hulled canoe that sailed more than 2,300 miles from Hawaii to Tahiti using only ancestral wayfinding techniques.

Somsen, who served in the U.S. Marine Corps before joining the Hokulea crew, described the journey as a revival of ancient navigational practices–methods that relied entirely on natural signs such as stars, ocean swells and seabird behavior. The crew completed the voyage without GPS, compass or modern instruments, relying instead on knowledge passed down orally through generations.

“We were out there with nothing but the sky and the sea,” Somsen said. “No electronics, no charts–just the stars and what Mau had taught us.”

The voyage was part of an experimental archaeology project led by Hawaiian artist and historian Herb Kawainui Kane, who co-founded the Polynesian Voyaging Society in 1973. Kane sought to challenge academic theories that suggested Pacific islanders had settled the region by accident, drifting on ocean currents without the ability to navigate intentionally.

To test this, Kane designed Hokulea based on 18th-century sketches from Captain James Cook’s expeditions. The canoe’s name refers to the star Arcturus, which passes directly overhead the Big Island of Hawaii and served as a key navigational marker for ancient voyagers.

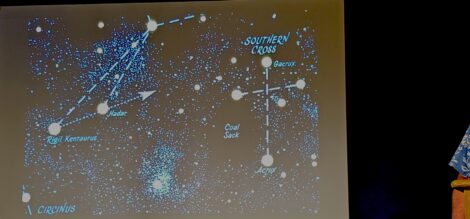

The Southern Cross constellation at 184 degrees (4 degrees west of due south), with pointer stars Alpha and Beta Centauri. Traditional Polynesian navigators use these celestial markers to guide voyaging canoes like the Hōkūleʻa across vast Pacific distances.

Somsen was selected for the voyage as part of a cultural and scientific effort to retrace the migratory paths of Polynesian ancestors. The expedition aimed to demonstrate that long-distance ocean navigation was not only possible without modern tools, but had been practiced successfully for centuries.

Central to the voyage’s success was Mau Piailug, a master navigator from the Micronesian island of Satawal. Piailug was discovered through a Peace Corps volunteer who noted his expertise in traditional fishing and navigation. He agreed to train Nainoa Thompson, a young Hawaiian who would become the first native Hawaiian in centuries to complete a voyage using traditional wayfinding.

“Mau didn’t use maps,” Somsen said. “He had the ocean memorized. He could feel the swells and know where we were.”

Piailug used a mental star compass composed of 32 directional points, each with Hawaiian names. He recited these positions twice daily, relying on memory and observation rather than written records. His teachings emphasized the importance of environmental cues–patterns in the sky, sea and wildlife–that could guide a vessel across vast distances.

Navigators memorized more than 200 stars and their rising and setting positions. Orion’s belt star Mintaka was used to determine east-west orientation, while the North Star and the Southern Cross provided north-south bearings. During equinoxes, the sun’s position offered additional guidance, rising due east and setting due west. A first-quarter moon near the equinox could also help determine direction through its terminator line.

Ocean swells played a critical role in navigation. Long-range wave patterns often persisted for days or weeks in consistent directions. Changes in swell behavior could indicate the presence of nearby islands disrupting the flow. Seabirds offered further clues–certain species fly only 10 to 40 miles from land, departing each morning to feed and returning at night. Their flight paths helped navigators identify land even when it was not yet visible.

“There were nights when the stars felt close enough to touch,” Somsen said. “You realize you’re part of something ancient.”

The voyage from Hawaii to Tahiti took 32 days. The crew arrived just nine miles off target in the Tuamotu island chain before continuing on to Tahiti. Somsen described the precision of the navigation as “remarkable,” given the absence of modern tools and the challenges faced along the way.

One of the most difficult stretches came near the equator, where the crew spent nearly a week stalled in the doldrums–a region known for unpredictable wind patterns and extended periods of calm. Located near the Intertropical Convergence Zone, the doldrums can trap sailing vessels for days with little to no wind, making progress difficult and testing navigators’ patience and resourcefulness.

“We were just sitting there, waiting for wind,” Somsen said. “It was hot, quiet and endless. That’s when you really learn to trust the ocean.”

The voyage also began with a storm, with winds reaching 40 to 45 knots on the first night. Despite these conditions, the crew maintained course and relied on traditional techniques to stay oriented and safe.

Somsen reflected on the emotional and cultural weight of the journey. “Hokulea wasn’t just a canoe,” he said. “She was a living link–between islands, between generations, between ways of knowing.”

The return voyage from Tahiti to Hawaii took 25 days. It marked the first time in approximately 600 years that a Hawaiian navigator had completed such a journey using ancestral methods. The success of the expedition provided definitive evidence that Polynesian navigators possessed sophisticated knowledge and skills capable of intentional long-distance travel across the Pacific.

Since the 1980 voyage, Hokulea has undergone multiple reconstructions and continues to sail as part of the Polynesian Voyaging Society’s educational mission. The vessel recently completed a Pacific circumnavigation, visiting dozens of ports and sharing the story of traditional navigation with communities around the world.

In Hawaii, schools now teach seamanship and wayfinding to students as early as preschool, integrating cultural history with hands-on learning. The revival of these practices has helped reconnect younger generations with ancestral knowledge and fostered a renewed sense of pride in Polynesian heritage.

Books documenting the voyage include Sea People by Christina Thompson and Hokulea Rising by Sam Low. Both works explore the history and significance of Polynesian seafaring, offering detailed accounts of the Hokulea expeditions and the navigators who made them possible.

Somsen’s presentation at the New Ulm Public Library highlighted the enduring legacy of traditional navigation and offered insight into the cultural revival sparked by the Hokulea voyage. His reflections connected ancestral knowledge with modern curiosity, inviting listeners to consider the ocean not as a barrier, but as a pathway shaped by memory, observation and trust.

“You don’t look down at a chart,” Somsen said. “You look up. You memorize the stars, feel the swells, watch the birds. You become part of the ocean. That’s how you find your way.”

- New Ulm Marine veteran Stephen Somsen explained celestial navigation and wayfinding methods used by Polynesian voyagers during his presentation Monday night.

- The Southern Cross constellation at 184 degrees (4 degrees west of due south), with pointer stars Alpha and Beta Centauri. Traditional Polynesian navigators use these celestial markers to guide voyaging canoes like the Hōkūleʻa across vast Pacific distances.