Making money the illegal way

Retired Secret Service agent gives history lesson on counterfeiting

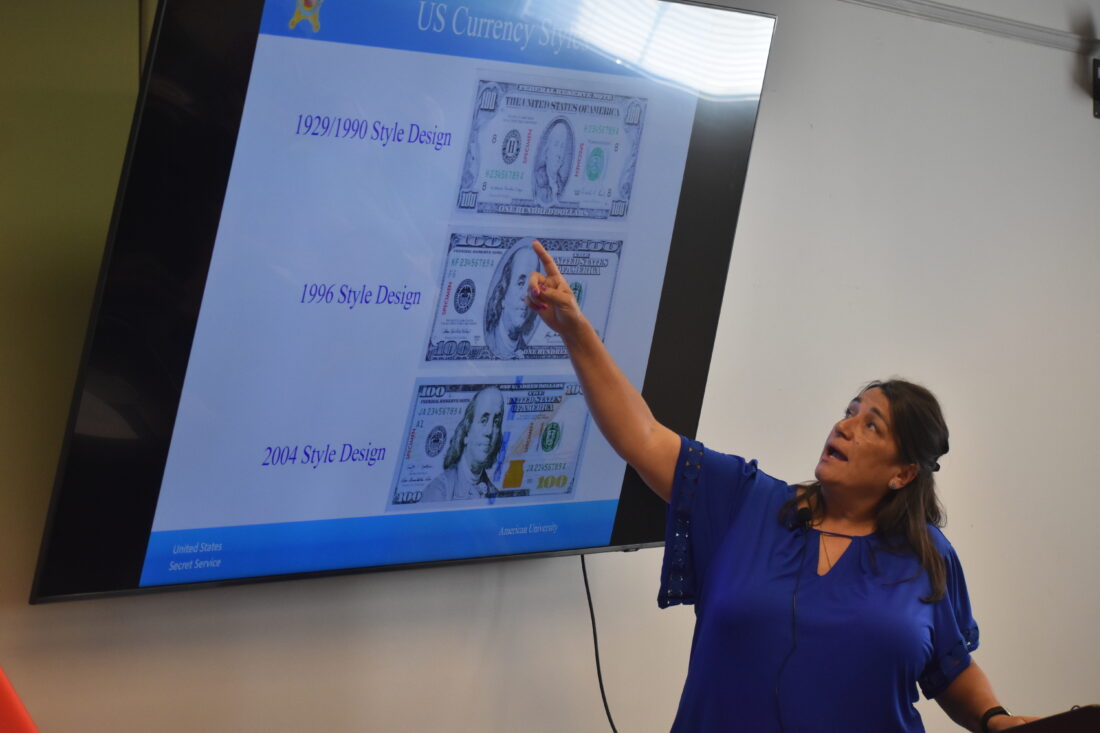

Retired United States Secret Service agent Julie Ferrell explains the three major changes made to currency. The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 created a standardize currency design, by 1929 enough of the new currency was in circulation to discontinue the previous bills. The 1929 design (top) remained in place until 1996. The 1996 design (middle) saw bigger heads on the currency. In 2004, another redesign (bottom) was issued with additional security measures.

The lunchtime crowd received a history lesson on counterfeiting from retired U.S. Secret Service agent Julie Ferrell.

The presentation was part of the Brown County Historical Society’s “Lunch and a Bite of History” series.

Ferrell, originally from Fairfax, MN, has spent most of her life working for the U.S. Secret Service. She first got involved with the Secret Service while attending college in Albuquerque, New Mexico. At that time, she was attending school to be a teacher, but after working in the Secret Service’s Albuquerque office for a few year as a part-time job, a manager recommended she take the agent test, which she passed. She began her work as an agent in Albuquerque but eventually moved to Washington, D.C. She retired as an assistant agent-in-charge in 2021. After retiring, she moved back to her home in Fairfax and began volunteering at the Brown County Historical Society (BCHS).

Ferrell agreed to give a presentation on her work with the agency, but also tell the story of a counterfeiting scheme that began in Brown County almost 95 years ago in the early 1930s.

Ferrel began the presentation by asking the audience what major historic incident occurred on April 14, 1865? This is the date Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, but it was also the date the Secret Service was first mentioned by the U.S. government.

Attendees of Thursday’s Lunch and a Bite of History presentation at the Brown County Historical Society museum annex learned a quick way to test the legitimacy of their cash. Former U.S. Secret Service agent Julie Ferrell said American currency is printed on a paper made from linen/cotton. The material includes red and blue fibers. If a bill is genuine, the fibers could be pulled up by scratching it with a paperclip.

The Secret Service’s original mission was not to protect the U.S. President; it was to protect the country’s economy by combating counterfeiting that was running rampant at the end of the Civil War. It was estimated that as much as one-third of the nation’s currency was fake. Within a year of establishing the Secret Service, agents had captured more than 200 counterfeiters and destroyed multiple counterfeit printing plants.

The agency evolved over the years and after President William McKinley’s assassination in 1901, their mission expanded to presidential protection but the agency’s anti-counterfeiting work continued.

In the early 1930s, Brown County became the center of a relatively sophisticated counterfeiting scheme. Over a two-year period, three individuals would be responsible for floating thousands of fake bill across six states in the Midwest.

The counterfeiting scheme began in Essig, Minnesota, with Raymond Marti and Emil Winkelmann. Later, Emil’s brother William would also join in the money making racket.

Marti was a Mankato native, but during the 1920s, he worked for the Sleepy Eye Herald-Dispatch as a reporter and handyman. At one point, he and his boss at the Herald attempted to buy the Fairfax Standard but could not make a deal.

By 1930, Marti was unemployed with a family to support. He visited his friend Emil Winkelmann, who worked at the Essig Bank. Emil Winkelmann had served as a cashier at the Sleepy Eye and Essig banks and would even become the manager at Essig Bank until it closed in 1932.

Marti asked Emil if he “knew of a way to make some money.”

Emil then pulled out a $10 bill from the register and asked Marti, who had worked as a commercial artist, if he could make one.

As a bank employee, Emil Winkelmann had been trained on how to detect fraudulent currency. He would use the skill to avoid getting caught. Marti was able to use the skills he had from working at the Sleepy Eye Herald-Dispatch to work the printing press used to create the fake currency.

In 1931, Winkelmann and Marti began passing the fake currency. The two would make the fake money on a weekend, then during the week travel outside of the community to spend it. They would buy small items with the bills to get back real change. Since they were this outside of their home community, by the time anyone realized the money fake, they were already gone.

They conducted this operation for a year until the Essig bank closed in May of 1932. The counterfeiting equipment was moved to Mankato and William Winkelmann joined in the scheme. William had worked as a bank cashier in Searles, but that had also closed.

A second printing press was added to the operation. The Winkelmann brothers considered cutting Raymond out of the money-making operation, but they did not know how to work the press.

“Their goal was not to make a ton of money,” Ferrell said. “They wanted to be comfortable enough to live for two or three years.”

The Secret Service became aware that someone in the Midwest was circulating counterfeit cash as banks began turning it in, but they had no idea who was behind it.

Ferrell said the only thing they could do was setup agents in small towns where they floated the bills in hopes of catching them in the act.

For two years, the men passed the fake bills throughout southern Minnesota, the Dakotas, Wisconsin, Iowa, Missouri, Kansas and even the West Coast.

The counterfeiting operation came to an end in Sept 1933. The Winkelmann brothers were in Monroe, Missouri, trying to pass counterfeit money at a drug store, but the shopkeeper realized it was fake cash because the serial numbers matched a warning they had received from the Secret Service.

He told the men he was unable to make change and told them to try another drug store. The shopkeeper alerted the local St. Louis office of the Secret Service and the men were detained.

The Winkelmann brothers confessed to the operation and soon the counterfeiting equipment was seized in Mankato. Around $37,000 in counterfeit money was seized at the Winkelmann’s home. Marti was also apprehended later in New Richmond, MN. At the time of his arrest, he had $20 in fake bills on him. Another $7,260 in counterfeit money was found at Marti’s residence in Mankato.

At the time of the arrest, passage of one counterfeit bill carried a 15 year prison term and $5,000 fine. Each bill passed counts as a new offense.

Ferrel said that had they been given the maximum sentence, the men would have served over a thousand years and needed to pay back over $1 million in fines. In the end, all three men received relatively lenient sentences.

The Winkelmanns were tried in Minnesota and Missouri for the crimes. Emil Winkelmann received two three-year sentences in each state and a $500 fine. William Winkelmann received three years for the Minnesota charges and a year and a half in Minnesota, as well as a $500 fine.

Marti received two years in federal prison and $500 fine. There is no record of him being sentenced in St. Louis. All three men spent their first prison sentence at Leavenworth Federal prison in Kansas.

Asked why the men received relatively lenient sentences, Ferrel believed the judge was moved by their plight. During the sentencing, the judge acknowledged the Winkelmann brothers had both served their country in WWI. They had also lost their banking jobs due to bank closures. The Great Depression had left many struggling to make money.

Marti also received support from his former employers at Sleepy Eye Herald-Dispatch. An editor had written a letter on his behalf, speaking to his character.

Ferrell reported that after Emil Winkelmann served his time, he began working as an electrician in Minneapolis. It was a trade he learned at Leavenworth prison. He would remain an electrician the rest of his life. After his death, he would be buried in Fort Snell Cemetery.

Following the presentation, Ferrel took questions from the audience and gave simple tips for checking currency. She was asked if the Secret Service was updating tactics related to fake cryptocurrency. Ferrel confirmed there was a department that investigated crypto-currency as it seemed to be the direction currency was going, with some physical money being phased out. She said it was possible the penny could be discontinued, as it cost more to make pennies than they were worth.

Ferrell ended the program by saying that if a person comes into possession of counterfeit currency, it should be turned over to a bank or law enforcement.

“Possession of fake bills is illegal,” she said.

- Retired United States Secret Service agent Julie Ferrell explains the three major changes made to currency. The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 created a standardize currency design, by 1929 enough of the new currency was in circulation to discontinue the previous bills. The 1929 design (top) remained in place until 1996. The 1996 design (middle) saw bigger heads on the currency. In 2004, another redesign (bottom) was issued with additional security measures.

- Attendees of Thursday’s Lunch and a Bite of History presentation at the Brown County Historical Society museum annex learned a quick way to test the legitimacy of their cash. Former U.S. Secret Service agent Julie Ferrell said American currency is printed on a paper made from linen/cotton. The material includes red and blue fibers. If a bill is genuine, the fibers could be pulled up by scratching it with a paperclip.