‘The river will not wait’

Engineers say river flooding on the rise

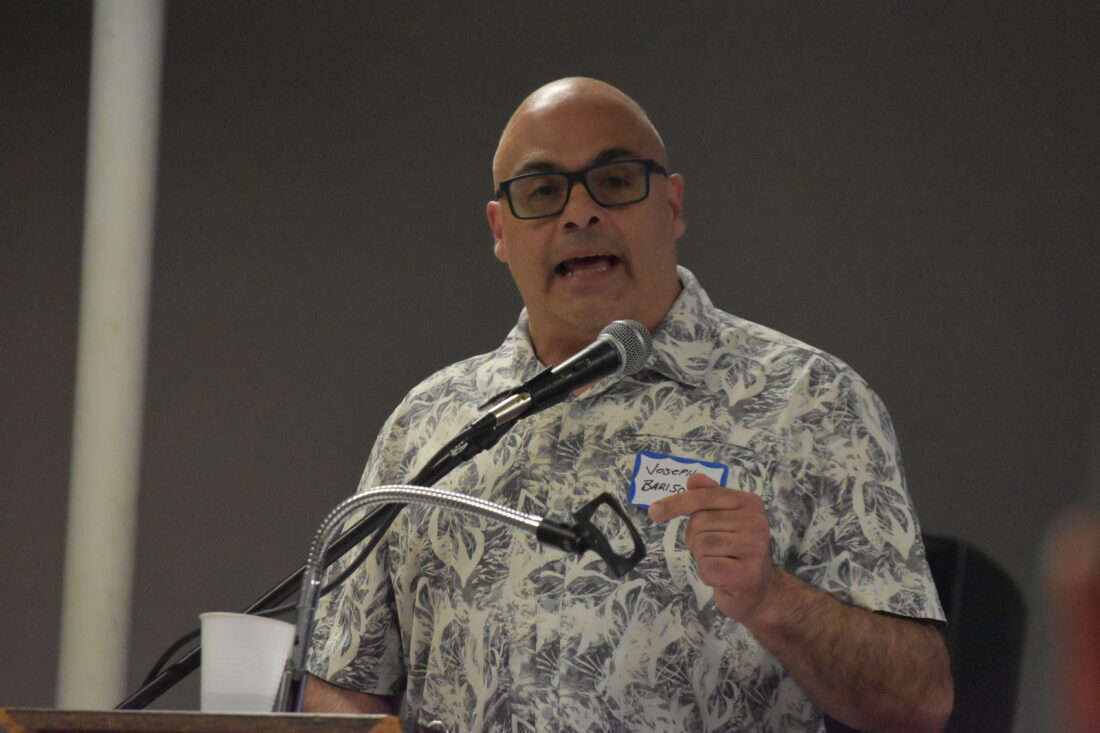

Staff photo by Fritz Busch Izaac Walton League of American Minnesota Vice President Joseph Barisonzi told River Congress attendees the Minnesota River challenges won’t wait for policies, paperwork and politics.

MANKATO — Minnesota River improvement advocates said a system wide approach is needed to improve the Minnesota River watershed that is changing due to man-made and natural causes.

“The river will not wait. Not for our politics. Not for our process. Not for our patience,” said Minnesota Izaak Walton League Vice President Joseph Barisonzi at the 17th Minnesota River Congress at the Kato Ballroom Thursday.

The Minnesota River Congress is a citizen-led organization focusing on natural resources and economic health of the Minnesota River basin. It’s mission is to promote citizen participation from all communities of interest and take cooperative action to protect, conserve and improve the Minnesota River system.

“We have known this since the first River Congress. We know it even more urgently today. I rise to offer a call, because if we are serious about saving the river, we must act like it,” he said.

Barisonzi said the problem is bigger than any one project and a system-wide approach is needed to deal with it.

“Look at the price tags,” he said. “The Henderson flood wall and road raise–$26 million. Shakopee’s flood protection plan and storm water management projects–over $10 million. The Rapidan Dam breach emergency response and clean-up–over $25 million so far, with long-term repairs likely to cost $100 million or more.”

Barisonzi said the project improvement planning framework needs to change. He said the Board of Water & Soil Resources (BWSR) requires watershed plans center on implementation tables, listing projects prioritized for funding, not on system resilience or policy change.

He said pages of project line items leave system governance and resilience strategies blank or vague.

“The Minnesota River is a vast, dynamic system, shaped by climate-driven hydrology that is changing faster than our response,” said Barisonzi. “Warmer winters, flashier rains, intensified runoff patterns, forces are overwhelming piecemeal solutions.”

He said 60,000 miles of tile drainage lines funnel water straight into the Lower Minnesota River watershed, bypassing natural soil filtration, speeding up runoff and carrying phosphorus, nitrogen and sediment.

“In Blue Earth County, one inch of rainfall on one square mile of tiled land produces over 17 million gallons of runoff,” said Barisonzi.

He said other pollution and impactful land-use changes include PFAS (man-made, industrial forever chemicals) and wastewater plants unaccountable for removing pharmaceuticals.

“The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) reports 88% of the Minnesota River fails basic turbidity standards (that measure water clarity and indicate suspended particles),” said Barisonzi. “We must shift from project-by-project reviews to a cumulative impact mindset.”

District 7 MnDOT Maintenance Engineer Scott Morgan presented photos of Minnesota River floodwaters topping Highway 169 near the Mankato Happy Chef Restaurant, between St. Peter and Le Sueur, and four to five feet of floodwater on State Highway 93 between Le Sueur and Henderson.

“These are the highest water levels ever on some roads built to handle 100-year floods,” said Morgan.

Minnesota Board of Water and Soil Resources Executive Director John Jaschke said a lot of Minnesota River watershed project improvements have happened in the last decade.

“We created water improvement plans in 2015. Now, every major state watershed has an improvement plan. That is a significant achievement,” he said. “Stay focused. There is still a lot of work to do. Federal funding is now being questioned. We can improve drainage and water quality in the same place. We have to balance needs with what is reasonable. We could design for 500-year flood situations, if we could afford it.”

Flood event data shows 12 of 22 major Minnesota River flood events in the past 90 years occurred since 2010.

In 2017, a modest volunteer effort began to address water quality by examining Minnesota River watershed drainage improvement projects. Gathering documents including project petitions, engineering reports, public comments and Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) advisory letters, the effort grew to become the Minnesota River Collaborative.

It now includes the Lake Pepin Legacy Alliance, Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy and Minnesota Well Owners Organization.

Seeking other interested organizations, the collaborative proposes legislative to improve drainage regulation and oversight and encourages funding efforts to avoid adverse effects and consider cumulative impacts of drainage projects.

For more information, visit www.mnrivercongress.org.